It’s not a right if you aren’t allowed to do it.

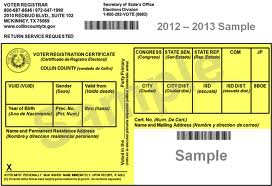

Still the only voter ID anyone should need

A day before Texans go to the polls, an unusual group gathered for lunch at a Mexican restaurant not far from downtown: an unemployed African-American grandmother; a University of Houston student originally from Pennsylvania; a pregnant mother who had recently moved back to the area with her family; and a low-income white woman who struggled to make eye contact and kept her money in a pack strapped around her waist.

They had not met each other before, but they had one thing in common: Thanks to Texas’s strict voter ID law, they all faced massive hurdles in casting a vote. Over fish tacos and guacamole, they shared their stories—hesitantly at first, then with growing eagerness as they realized they weren’t alone in being victimized by their state.

Lindsay Gonzales, 36, has an out-of-state driver’s license, which isn’t accepted under the ID law. Despite trying for months, she has been unable to navigate an astonishing bureaucratic thicket in time to get a Texas license she can use to vote. “I’m still a little bit in shock,” said Gonzales, who is white, well-educated, and politically engaged. “Because of all those barriers, the side effect is that I don’t get to participate in the democratic process. That’s something I care deeply about and I’m not going to be able to do it.”

As Texas prepares for its first high-turnout election with the voter ID law in place, the state has scrambled to reassure residents that it’s being proactive in getting IDs to those who need them, and that few voters will ultimately be disenfranchised. But those claims are belied by continued reports of legitimate Texans who, despite often Herculean efforts, still lack the identification required to exercise their most fundamental democratic right.

There’s a depressingly long list of people who have been disenfranchised by Texas’ law at the end of the article. Not theoretical possibilities, real people who were not allowed to vote. There are more and more of these stories out there as well. I’d love for Greg Abbott and Rick Perry and the six Supreme Court justices who thought letting this election proceed with that law in place despite its documented effects to have to look each one of these people in the eye and explain to them why this was necessary. Because the law is working as intended. What happened to these people was a feature, not a bug.

But they could have gotten free election IDs, I hear you say. Maybe, if they knew about that under-publicized option. And if they were able to navigate the bureaucracy successfully and pay their poll tax at the end.

Every document Casper Pryor could think of that bore his name was folded in the back pocket of his jeans. But sitting on a curb Thursday, a can of Sprite in hand, Pryor wasn’t sure whether those papers and the hour-long bus ride he had taken to get to Holman Street would result in a crucial new piece of ID. An ID that would allow the 33-year-old Houston native to vote.

Election identification certificates were designed for the 600,000 to 750,000 voters who lack any of the six officially recognized forms of photo ID needed at the polls, according to estimates developed by the Texas secretary of state and the U.S. Department of Justice. Legislators created the EICs, which are free, in part to quell criticism that enforcing the state’s much-litigated ID law amounted to a poll tax that could disenfranchise low-income and minority voters.

But as of Thursday, only 371 EICs had been issued across Texas since June 2013. By comparison, Georgia issued 2,182 free voter ID cards during its first year enforcing a voter ID law in 2006, and Mississippi has issued 2,539 in the 10 months its new law has been in place. Both states accept more forms of photo identification at polls than Texas does, so fewer voters there would need to apply for election-specific IDs.

In Texas, some would-be voters are hitting roadblocks.

Pryor said he has been spending more than four hours each trip trying to obtain an EIC, and he’s been back and forth several times. Though the cards are free, there are transportation costs and fees for supporting documents.

“It turned into a full-time job,” he said. “Going here, going there, it’ll make you give up.”

[…]

Some voters decided to pursue a Texas state ID card instead of an EIC. The requirements are similar, but the state ID can be used for more purposes than elections.

Money factors in the decision.

Applying for a Texas state ID costs $16, and if an individual does not have a birth certificate, getting that costs another $22. For those who want an EIC, a birth certificate can be obtained for a discounted price of no more than $3.

Another difference: EICs do not require a background check, while a Texas state ID does. For low-income applicants concerned about unpaid traffic tickets, that can be enough to decide on an EIC, said Marianela Acuña Arreaza, the Texas coordinator of VoteRiders, a nonpartisan nonprofit helping eligible voters cast ballots and not engaged in the ongoing litigation.

“Voting is not a luxury item,” Acuña Arreaza said. “It should be something you should be able to do because you’re a citizen and you’re eligible.”

[…]

Abbie Kamin, through the Campaign Legal Center, has been working with people who want to vote at the polls, sometimes driving an hour out of the city to obtain a birth certificate and accompanying them for lengthy waits in DPS offices. The center’s executive director was an attorney for the plaintiffs in the voter ID case, but Kamin’s work is ground-level. Beyond the transportation hurdles and costs for some voters lacking ID, there has been confusion among agencies and individual clerks, she said.

“I’ve had another woman working with me who called the DPS three different times and gotten three different answers,” Kamin said.

During a federal court trial that concluded in Corpus Christi in September, the judge found that the DPS process for granting EICs lacked consistency.

When asked if any training had since been provided, DPS spokesman Vinger responded, “No.”

Training costs money, don’t you know. Greg Abbott wants to take the gas tax money that currently goes to DPS and use it for road building. That means DPS will have to compete with other budget items to get general fund money. What do you think are the odds that extra funds for EIC training would be included in that?

The good news is that Casper Pryor did eventually win the game of running the DPS gamut, and in the end he got his EIC, making him one of the lucky few to do so. One wonders what the reaction would be if a random sampling of voter ID supporters had to go through what he went through to get to do what they take for granted. To end this post on a positive note, here’s another story about people who worked a lot harder to be able to vote than you and I did.

April Fisher walked into a brightly lit, flag-adorned room at the Harris County Administration Building on Wednesday and, for the first time in her life, contemplated a ballot.

“I’ve never voted in my life,” the 30-year-old Louisiana native said with a shrug. “I don’t even understand politics.”

Fisher came to Houston five years ago after her father gambled away their family’s life savings. The choices she made here ended in addiction, prostitution and criminal convictions.

But on this day, with her life on the mend, Fisher found the name of the judge who heard her most recent prostitution charge, a woman she credits with helping get her life back on track. She tapped the voting machine’s selector dial. It felt good.

In a booth next to her was the kind of authority figure who had been an adversary in Fisher’s past life – a sheriff’s deputy.

“I was proud to stand next to that deputy and he didn’t put handcuffs on me,” she said.

Fisher walked out of the downtown building and into a balmy fall day minutes later.

“I feel like my voice was being heard,” she said, before lighting up a cigarette.

A precious right for many Texans, voting for Fisher and a group of about 15 women – recovering drug addicts, former sex workers and others – was about something more: finding their voice.

They were enrolled in (or have graduated from) the “We’ve Been There Done That,” a program run through the Harris County Sheriff’s Office, which seeks to rehabilitate women and help them avoid returning to their criminal past.

“These women have never been empowered, have been victims of sex abuse, of abuse, of imprisonment,” said Jennifer Herring, director of re-entry services for the Sheriff’s Office. “Now, for them to be able to seek for themselves a voice through this voting process, it’s liberating.”

Read the whole thing. No matter how you feel today about the election, I trust that story made you feel a little better.

Again, not one shred of evidence that voter ID disenfranchises anyone, just anecdotes about how stupid people can’t follow simple instructions.

For the woman who had a California DL and “had to navigate an astonishing bureaucratic thicket” I know at least 50 people who moved here from other states and had a TDL in a single visit to a DPS office. It’s just not that hard.

From the article, there was a guy whose birth certificate had a different name. Did anyone tell him that the name on that document is your real name?

I do think the 60 day expiration limit ought to be changed. College students ought to vote at home, not where they go to school.

There are plenty of college students for whom their address at school really is their home. The rest still have a stake in what sort of services and laws the place where they live most of the year operates under.

The 60 day expiration could be relaxed without risking lots of fraud.