If this story was meant to evoke my sympathy, I’m afraid it failed.

Since the hospital closed in Paducah, a town 30 miles to the north, patients in Guthrie have 60 long miles to travel to Childress for care. It’s a feeling of isolation that has crept up on other rural corners of the state following a spate of 10 hospital closures in the past two years. And financial data collected by the state and federal government shows revenue is falling for other rural hospitals, suggesting more may be on the brink.

Policymakers, operating on tight budgets, must decide whether they are willing to spend more money on small hospitals serving a limited number of patients, hospitals that in most cases could not keep their doors open without government assistance. But without them, people, inevitably, will die.

“We’ve all seen the crash that’s coming in the next five years,” said Kell Mercer, an Austin-based lawyer who has worked on hospital bankruptcy cases. “The Legislature’s more interested in cutting revenue and cutting services than providing the basic services for these rural communities. This is a perfect storm of events that’s going to hit the state, hard.”

Texas’ rural hospitals have long struggled to stay afloat, but new threats to their survival have mounted in recent years. Undelivered promises of federal health reform, payment cuts by both government programs and private insurers, falling patient volumes and a declining rural population overall have been tough on business — a phenomenon one health care executive called “death by a thousand paper cuts.” Add to that Texas’ distinction as the state with the highest percentage of people without health insurance and you get a financially hostile landscape for rural hospital operators.

“Hospital operating margins, and this is probably true of the big guys and the small guys, too, are very small, if not negative,” said John Henderson, chief executive of the Childress Regional Medical Center. “In a way, Texas rural hospitals are kind of in a worst-case scenario situation, because we lead the nation in uninsured, and we took Medicare cuts hoping that we could cover more people.”

[…]

The sum of all these changes has people like Don McBeath, who lobbies for rural hospitals, warning of a repeat of the widespread hospital closures Texas experienced three decades ago. In 1983, the federal government restructured the way Medicare made payments to hospitals, meant to reward efficient care. Those changes proved untenable for small hospitals with low patient volume, heralding decades of closures that claimed more than 200 small Texas hospitals as casualties, McBeath said.

Some counties can afford to raise taxes to keep their hospitals open; others cannot, or find that raising taxes is politically impossible.

And when a small county hospital closes, often the hospital in the next county over must shoulder a bigger burden of uninsured patients. Even patients with insurance face higher deductibles and often can’t pay their bills.

“When it closes, you’re forced to make other decisions, other plans,” said Becky Wilbanks, a judge in East Texas’ Cass County, which saw a hospital closure last year. “That’s an economic hit that we took.”

Rural hospitals are often one of the biggest and highest-paying employers in a community, Wilbanks said.

And when they close, it can have a domino effect on other local businesses, said Hall County Judge Ray Powell. When his county’s hospital closed in 2002, it prompted the local farm equipment dealership to close its doors and move to Childress.

“It was a big loss,” he said. “It was devastating.”

Across Texas, rural counties are seeing their populations dwindle. King County, home to Guthrie, is one of Texas’ 46 rural counties that are projected to lose population over the next four decades — at a time when the rest of the state’s population is expected to double.

Maybe I’m just a jerk, but my first reaction to stories like this is to check the most recent election results in the counties named.

In Cass County, Greg Abbott got 74.64% of the vote.

In Hall County, Greg Abbott got 85.09% of the vote.

In King County, Greg Abbott got 96.77% of the vote. Ninety-three people voted in total, and 90 of them went for Abbott.

In other words, the voters in these counties have gotten what they voted for. Perhaps someone should point that out to them if and when more of these rural hospitals close.

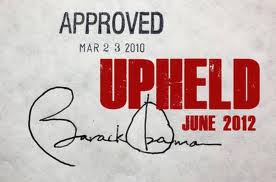

This isn’t entirely fair. Declining population in these counties is nobody’s fault. A change in Medicare payments in 2002 caused a lot of upheaval. But the problems they’re facing now are entirely the result of Republican intransigence on Obamacare and hostility to Medicaid. It’s abundantly clear by now that Medicaid expansion has been a boon for the states that have done it, while states like Texas are feeling the downside good and hard. If you want to blame Wendy Davis for not adequately communicating the issue to these voters, you have to equally blame Greg Abbott for continually lying about the need for “freedom” from the “tyranny” of Obamacare. Elections have consequences. This is one of them.