Houston drivers are facing more than a dozen years of work on freeways in and around the central business district — at a cost that could come close to or exceed $6 billion.

All that work, however, will not significantly affect commutes for months or even years. Once it does, construction could lead many to rethink their usual routes.

[…]

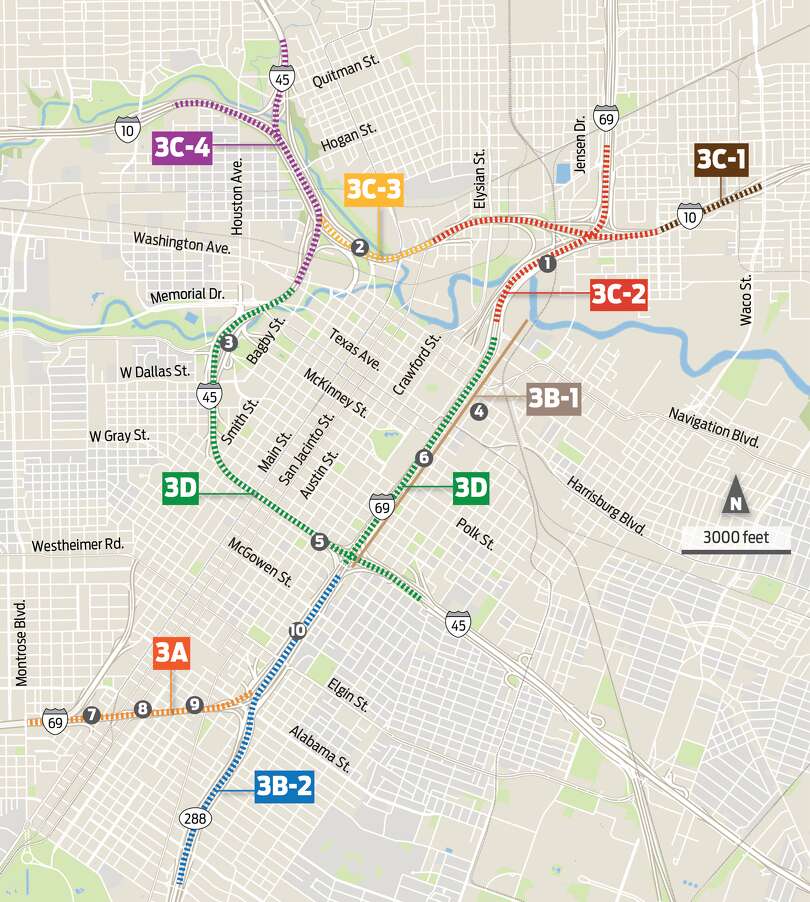

The freeway work around downtown is broken into eight segments, many that will overlap, leading to successive potential bottlenecks. Because the larger I-45 has three main segments, all of the projects downtown comprise Segment 3. The downtown projects are broken alphabetically and numerically into smaller projects, each a separate job that TxDOT will award to a construction company.

Notable changes include:

1. Straighten Interstate 69 and widen from eight to 10 or 12 lanes in each direction.

2. Straighten and add two express lanes in each direction for traffic not headed toward downtown.

3. Replace the Pierce Elevated with downtown connectors and shift Interstate 45 to east side of central business district.

4. Add new local street between Commerce Street and Leeland Street to increase options from central business district to EaDo.

5. The Pierce Elevated would no longer serve a transportation function and could be removed/repurposed.

6. Structural cap built atop I-69 depressed section from Lamar Street to Commerce Street east of the George R. Brown Convention Center (developed by entity other than Texas Department of Transportation).

7. Structural cap built atop I-69 depressed section from Wheeler Transit Center to Fannin Street (developed by entity other than TxDOT).

8. Structural cap built atop I-69 depressed section from Main Street to Caroline Street (developed by entity other than TxDOT).

9. Structural cap built over I-69 depressed section from Almeda Road to Cleburne Street (developed by entity other than TxDOT).

10. Cross street reconfiguration for arch bridges at Elgin, Tuam and McGowen Streets.

All of the work along I-45, which could last into the 2040s before the portion near Beltway 8 is completed, is expected to cost around $13 billion, though increases in cost to the project have been common as general construction prices jumped during the COVID pandemic and costs of materials increased because of inflation. Less than a decade ago, officials announced the project at an estimated cost of $7 billion.

Always bet the over on the price tag estimates. I mean, as recently as September it was described as an $11.2 billion-plus rebuild. Plus another two billion dallors or so, apparently. At this rate it’ll be more than the national debt by 2040.

The effect of this multi-decade construction project on drivers has not yet been felt, but its effect on businesses and restaurants and real estate in general in the area has been. I expect there will be a lot more before it’s all said and done.

But that effect on drivers is coming. And when it does, if we were clever and forward-thinking enough, we could have taken advantage of it to maybe get a few people to try something different.

Commuters are creatures of habit—until, suddenly, they aren’t.

That is the conclusion of researchers, working at a number of institutions and across a variety of studies, who have examined when and why people reconfigure their journeys to regular destinations like offices and schools. Typically, travelers stick with whatever mode and route they are used to. But once in a while, an unusual event like a new job or a closed highway upends the status quo. Such disruptions can become inflection points, compelling commuters to alter travel habits that are otherwise entrenched.

Ordinarily, few people even contemplate adjusting their daily trips, regardless of other options. A 2016 study of the United Kingdom, where alternatives to driving are more plentiful than in the United States, found that only 1 in 10 car commuters shifts to another mode annually. But under certain circumstances, such changes become far more likely. The behavioral science of commuting holds powerful lessons for policymakers, civic leaders, and environmentalists hoping to convince drivers to instead use modes like public transit and biking that can ease gridlock, improve air quality, and mitigate climate change.

Switching from an SUV to using a new, direct, and protected bike lane might seem like a no-brainer—why not leave the hulking gas guzzler in the garage, if you can?—but it can take effort. “You might be going to work and not realize there’s a better option available,” said Ben Clark, an associate professor for transport planning at the University of the West of England, and an author on that 2016 study. In a sense, this narrow-mindedness is rational due to the myriad decisions people already juggle. “We haven’t got the mental space to be recalculating transportation options,” Clark said, shrugging.

[…]

For transportation, personally disruptive events present brief windows to influence future travel behavior. A 2016 study found that new UCLA students were less likely to drive and more likely to use public transportation if they received information about car-free options before arriving on campus. Other research has found that free transit passes are more effective than discounts at inducing mode shift. Based on those findings, one could imagine climate-conscious public officials offering a “welcome package” of transit and bikeshare passes to those who have recently moved into a new home. Employers looking to show a commitment to sustainability (and to keeping their parking lot uncrowded) could offer the same to new hires.Moments of discontinuity can also be triggered by external forces. In 2014, a monthlong strike in the London Underground scrambled many commutes, forcing passengers to find new routes to get to work. Researchers found that many straphangers ultimately preferred their “detour” to their traditional route, sticking with it even after the strike ended and normal service was restored. In effect, the strike prompted them to discover a better way to travel that had already been available to them. When it comes to cars, that finding suggests that a shock like a road closure might be enough to finally force people to take action and change how they commute.

In other words, if we’d had a plan in place to give the drivers who will be affected by this disruption full information about other options available to them, many of them would be open to trying them. I doubt there’s the time to do that now even if there were the will. But at least it could have been done.

Anyway. The story lays out the current timeline of the construction, with plenty of graphics to help you picture where it will be. Read ’em and be prepared to find an alternate route.

$10,000,000,000.oo+ on car infrastructure in central Houston.

How about Texas/TxDOT(?) provides some lagniappe for e-bike subsidies for central Houstonians? Get some of the cars off the road!

Making the Katy freeway the record holder for most lanes didn’t improve the traffic problems. The same will happen here, at the expense of all the current residents who will be shafted via eminent domain.