Some lessons for the future here.

A new report from the National Hurricane Center found that Hurricane Beryl roared into the upper Texas Gulf Coast with maximum winds of 92 miles per hour, just 3 miles per hour shy of being designated a Category 2.

Following the end of the Atlantic hurricane season on Nov. 30, the National Hurricane Center completed a thorough investigation of each tropical cyclone to account for any new data that may have been discovered. Among the data analyzed in the six months following Beryl was an aircraft-measured wind gust of 103 miles per hour roughly 8,000 feet above ground level and a peak wind gust of 97 miles per hour measured by a private Texas Tech University weather station.

Beryl was in an environment ripe for rapid intensification as it was on its final approach to the upper Texas Gulf Coast. Tim Cady, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service who covers Greater Houston and Galveston, says Southeast Texas would have likely been hit by an even stronger Beryl had its strengthening begun sooner.

“Beryl encountered a period of favorable conditions as it was approaching the upper Texas Gulf Coast,” Cady said.

Above normal sea surface temperatures and low levels of atmospheric wind shear, which is the change of wind speed throughout the atmosphere, contributed to Beryl strengthening again into a hurricane in the hours before landfall.

The marshy topography where Beryl made landfall may explain why Beryl took so long to wind down, and may have even contributed to some degree of intensification immediately following landfall. “We’ve seen in past storms that there can be a bit of intensification post-landfall if conditions remain favorable,” Cady says, referring to this phenomenon as the “brown ocean effect.”

There are several regions in the world where tropical cyclones have been shown to maintain or increase strength after landfall. The hypothesis is abundant moisture in the soil, whether caused by marshy terrain or days of heavy rain, help to “feed” a tropical cyclone as it passes over the saturated ground.

Beryl’s faster push inland simply meant it took longer to weaken since it was still in the process of strengthening as it came ashore. Had Beryl started to intensify earlier than it did, the results could have been an even more intense hurricane landfall.

That NOAA report is, at least as of Monday and despite the Muskian crime wave, here. This story is from two weeks ago and I had it on my to do list but got distracted, then I saw again and here we are. Space City Weather adds on.

While Hurricane Beryl was presumed to have a landfall intensity of 80 mph when it came ashore in Texas, the postseason review determined that this was too low. Beryl got an upgrade to a strong category 1 storm, with 90 mph maximum sustained winds at landfall. This is interesting, and it makes the comparisons to Ike somewhat more relevant in a data sense.

Ike came ashore as a weakening category 2 storm with 110 mph maximum sustained winds. Beryl came ashore as a strengthening category 1 storm, having rapidly intensified from a 60 mph tropical storm to a 90 mph hurricane in about 14 hours. While that’s still 20 mph of difference in maximum sustained wind, the fact that the two storms were trending in opposite directions, and all else the same, the weaker side of Ike wasn’t that much stronger than the “dirty” side of Beryl, which Houston experienced. This makes the similarities between the storms in terms of widespread tree damage and power outages more comprehensible in retrospect.

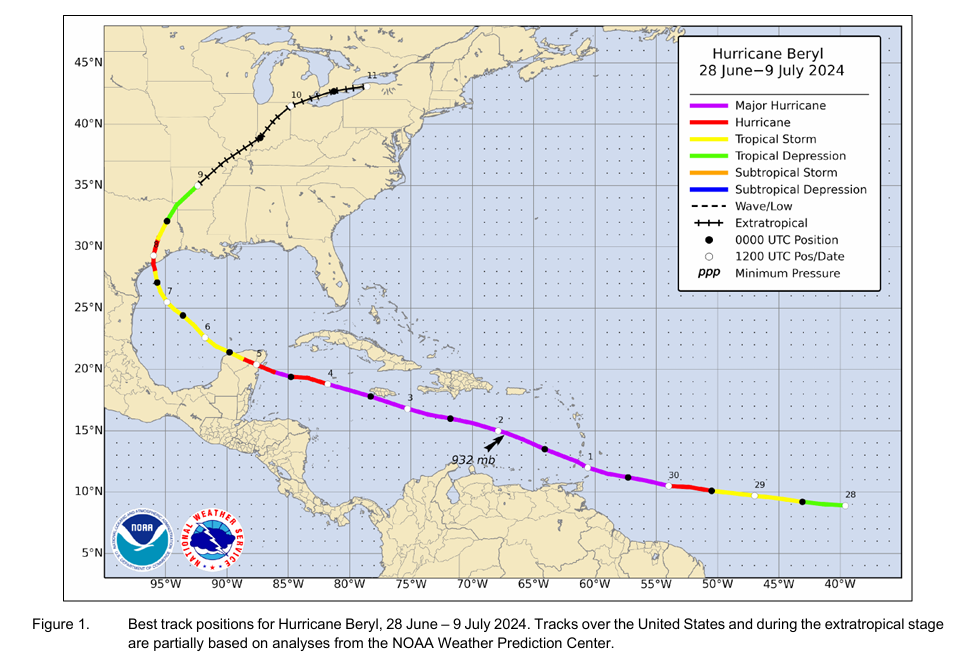

Also worth noting, Beryl peaked in the Caribbean as a category 5 storm with ~165 mph maximum sustained winds, confirming the intensity reported in the advisories. The report stated that “the maximum intensity of Beryl is somewhat uncertain due to temporal gaps in the aircraft data near the time of peak intensity, and issues with (microwave) surface wind estimates that prevented their use in this evaluation.” In other words, some of the data was unusable, and the timing of the reconnaissance flight into Beryl may have differed from the exact time of peak intensity. Whatever the case, 165 mph is dang strong.

[…]

We’ve said this countless times in the wake of Beryl and since: It was a warning to this region. Beryl had 14 hours of favorable conditions over water to strengthen and went from a tropical storm to nearly a category 2 hurricane. What if it had 24 hours, and started from a 70 mph tropical storm? 36 hours? We’ve seen this play out in Florida, Louisiana, and the Coastal Bend several times since 2017 with storms in the Gulf of Mexico. Harvey, Michael, Ida, Ian, Idalia, Helene, Milton to name some others. It really is a matter of when, not if. We need to continue to focus on ensuring we’re prepared every year with our hurricane kits, getting more people to adopt that practice, and continuing to invest in resiliency and infrastructure improvements, which is to say: Build the damn Ike Dike.

Hard to argue with that, but also hard to be optimistic about what the current federal government might do. The state has started to take some action, which is nice but also mitigated by its intense efforts to enable further climate change. Read the rest, read the report, and know what we’re up against.

What will a privatized NOAA/NWS be charging us for hurricane forecasts?