It could have been delayed till after the November election.

A federal judge in Corpus Christi ruled on Wednesday that a federal lawsuit challenging the legality of the state’s controversial Voter ID law is expected to begin in September as scheduled, 1200 WOAI news reports.

Civil Rights groups like the Mexican American Legislative Caucus, which is one of the groups fighting voter i.d., says it is very important that the law be thrown out before the November general election.

“We believe that conducting an election under a procedure that discriminates against the minority community would be wrong,” said Jose Garza, lead council for the MALC.

“We don’t want another election under a discriminatory election practice.”

Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos made that ruling official on Friday. The trial date is set for September 2. This what the plaintiffs, who hope to get a ruling against the voter ID law before the November election, wanted. The Justice Department had asked for the postponement on the grounds that discovery was taking too long, with the state trying to hide behind claims of legislative privilege. The DOJ had also filed a motion to compel the state to turn over a bunch of documents; Judge Gonzales Ramos gave the state a deadline to reply and scheduled a hearing for that on March 5. As with the redistricting lawsuit, Abbott is asking for a broad definition of what legislators and staffers don’t have to testify about, and as with redistricting, he deserves to be swatted down. In the meantime, another matter was settled.

Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos entered an order [Tuesday] afternoon adopting an agreement reached by the parties in Texas voter ID case to govern how complicated database matches will take place.

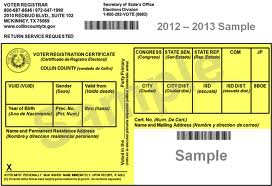

Under the agreement, the State of Texas will turnover – by Friday – information requested by the Justice Department in interrogatories from the state’s election database, DPS’ driver’s license and personal identification card databases, and the Texas concealed carry license database.

DOJ then will use the information provided to run searches to gauge what voters “have been issued a United States military identification card, certificate of naturalization, certificate of citizenship, passport or passport card, or veterans identification card” as well as whether a voter has “been determined by the Social Security Administration to have a disability, or by the Department of Veterans Affairs to have a disability rating of at least fifty percent.”

The Texas Election Law blog explains what that means, then considers the question of discovery and turning over documents that DOJ is asking for.

I speculate that DOJ and Texas are so far apart in their discussions of raw data in part because of differences in bureaucratic culture.

Assume for the sake of argument that members of the Texas Legislature collectively and intentionally planned to engage in the wholesale disenfranchisement of minority voters. In so doing, the lawmakers and their staff didn’t need any particular precision or careful data-based legal engineering. It was enough for them to intuit that any increase in the transaction costs associated with elections disproportionately affect the poor and minorities, as well as elderly and first-time voters. They didn’t actually need or want any data about the effect in detail, because the political purpose of the voter I.D. law isn’t to disenfranchise based on careful targeting. It’s to disenfranchise over the long haul.

It’s to put the thumb on the roulette wheel; to count cards at the blackjack table; to nudge the pinball machine without causing it to record a tilt. No subtlety or particular mathematical accuracy is needed or desirable (as any such accuracy would carry with it a discoverable paper trail, but more importantly, would actually cost money to create).

I don’t think the State of Texas is lying to hide its secret stash of high-level sociological evidence of voter disenfranchisement. It doesn’t have any secret stash of high-level sociological evidence of anything, because that would cost money.

Meanwhile, DOJ could argue to Texas with some despair, “you mean you passed a law without knowing what it would actually do?” To which the answer is “Yes. Of course. Have you actually been to our state lately?”

That makes an eerie amount of sense. We’ll see what the next hearing brings.