Our favorite pollsters aren’t optimistic about pot legalization despite some good looking poll numbers for it.

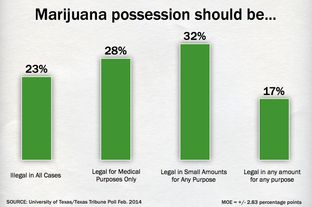

In the February 2014 University of Texas/Texas Tribune Poll, we asked respondents for their opinions on marijuana possession and gave them four options to choose from:

- “marijuana possession should not be legal under any circumstances;”

- “marijuana possession should be legal for medicinal purposes only;”

- “possession of small amounts of marijuana for any purpose should be legal;” and,

- “possession of any amount of marijuana for any purpose should be legal.”

Overall, just under a majority of Texans, 49 percent, said that possession of either a small amount or any amount of marijuana should be legal for any purpose. When combined with those who think marijuana should be made legal for medicinal purposes, 28 percent, it’s clear that the vast majority of Texans think that marijuana should be legal in some form. These results are comparable to national numbers, which show a slim majority of Americans favoring legalization.

But the overall results cloud the distinct ideological and partisan divergence over marijuana. Overall, 23 percent of Texas voters think that marijuana should be illegal in all circumstances, but opposition grows to 32 percent when we focus on Republican voters. Conversely, 77 percent of liberals think that small or large amounts of marijuana should be made legal for any purpose, but among conservatives, that support drops to 35 percent. Add the 32 percent of conservatives who would only legalize marijuana for medicinal purposes, and you see that the majority of the voters who drive elections in Texas remain clear-eyed in their opposition to recreational pot use.

This configuration of public opinion illustrates one reason (among the many possibilities) for some Democratic elites’ harsh attitudes toward Kinky Friedman’s candidacy for agriculture commissioner. However much potential there may be for the Democratic — and especially the liberal — grassroots to respond enthusiastically to Friedman’s emphasis on marijuana decriminalization, moderates and independents are evenly divided between those who are relatively restrictive (favoring, at most, legalization of medical uses) and those who are permissive (supporting legalization of some amounts for any use).

In the midst of a campaign in which Democrats need to persuade at least some non-Democratic voters in addition to mobilizing their own homegrown base, the talk about marijuana is at best a mixed bag, offering Republicans the opportunity to tar Democrats as cultural liberals among the far more numerous conservative and moderate voters.

This divergence of opinion between the different ideological poles is not as strong as we’ve seen in many other policy areas (abortion, for example), but there is a real distinction. This polarization in attitudes — along with the general trajectory of public opinion and the revenue that states like Colorado are pulling in — means there is reason to believe that this issue will be around for a while: There are political and policy reasons for even conservative leaders to consider some form of legalization, but also ideological points to be scored in public opposition.

Like other policy areas that have a potential moral component, such as gay marriage, opposition to decriminalization may turn out to be significant, particularly because it is concentrated in the very constituencies that buttress Republican dominance of elections and the legislative process in Texas.

I would look at it this way. There was widespread public support for changing Texas’ laws about beer distribution to allow microbreweries and brewpubs to sell their wares directly to the public and in retail outlets, but it took several legislative sessions for a bill to finally pass, and even then it was nearly derailed. What it took was mostly a matter of organization and lobbying, with some scaling back of the original legislation to earn enough support from former opponents. Though the opposition was limited to one lobbying group for the beer distributors that had no real argument for maintaining the status quo, they had money and power and it took a large show of force to overcome them.

In the case of pot legalization, we have decent public support but a fiercely determined opposition that likely won’t go away when they find themselves badly outnumbered, and as yet there’s no organization pushing legalization, just one renegade candidate that still has to win a runoff and a general election, and isn’t particularly well-liked in his party. There’s a decent chance that advances will be made to further decriminalize pot, as treatment and alternative forms of sentencing are much more popular these days than jail time, and there’s a conservative push for de-incarceration as a matter of fiscal policy. That’s not the same as legalization, of course, but it’s a large and solid piece of middle ground with a less determined opposing faction. When there’s a commercial interest in favor of pot legalization, that’s when we’re likely to see some real action, assuming such an interest is shown by the Colorado and Washington experiences to be viable. But as with casinos, that’s no guarantee, either. My advice to those interested in advancing this cause is to work on decriminalization. It gets you most of the way there, it’s achievable, it will keep people out of jail, and it will make it easier down the road to take the next step when and if public opinion becomes more firmly in favor. Advocating for medical marijuana is also probably a decent bet. But in the absence of even a rudimentary grassroots movement for legal pot, I wouldn’t expect anything more than that to be possible.

This makes me even more pessimistic (if that were possible) about restricting the payday lenders, expanding Medicaid, and — as you mentioned — casino gambling. One of the Houston weeklies says today that the horse racing interests are pushing Let Texans Decide again.