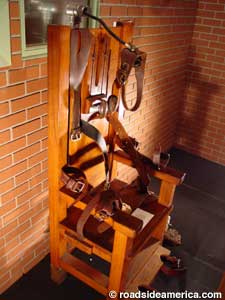

Perhaps nothing symbolizes this state’s swagger over being tough on crime like “Old Sparky,” an electric chair that was used to execute 361 inmates and is now the centerpiece of a prison museum.

It sits just minutes from the Texas penitentiary where it was forever unplugged 50 years ago this summer following the execution of Houston’s Joseph Johnson Jr. for murdering a grocer.

While the oak chair is now a capital punishment relic photographed daily by visitors, this state’s death row is undergoing what looks to be a historic shift.

Texas forged an international reputation as it has executed far more inmates than any other state in the nation since 1982, when it resumed capital punishment with lethal injection. But this year, Texas just may lose its distinction as the state carrying out the most executions annually, sitting in a three-way tie with Missouri and Florida. Each state has executed seven people so far this year.

In Texas, a slew of changes in capital punishment that have been trotted out over the past decade or so and are taking hold. Those include requiring better legal representation for people facing the death penalty, giving jurors the option of sentencing defendants to life in prison without parole, and increasing the use of DNA and other scientific testing. And significant to the change is the realization by lawmakers and others that the system that condemns someone is not bulletproof.

The state executed an average of 29 people annually from 1997 to 2007, with 40 in 2000, according to statistics maintained by the Death Penalty Information Center. But it is now on track to have no more than 11 this year, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, the fewest number in 23 years.

Texas is not getting weaker on crime, but getting smarter about who is sentenced to death by reducing the chances of condemning an innocent person, said former Texas Gov. Mark White.

“We are starting to recognize that being tough on crime doesn’t mean you have to be tough on innocent people,” White said. “We have learned a lot: use the cutting edge of science, and not just the fast draw of the Old West.”

Not sure how much credit I’m willing to give the Lege for this, other than the passage of life without parole, which has definitely had an effect. If there’s a greater awareness about wrongful convictions and the need to safeguard against them, it’s mostly due to the efforts of groups like the Innocence Project, local officials like Dallas County DA Craig Watkins, and the compelling stories of exonerated men like Michael Morton, Anthony Graves, and the late Timothy Cole. The fact that insufficient enthusiasm for the death penalty can still be used as a political attack suggests we haven’t come that far from the old days. Though I am not a death penalty abolitionist, I will be perfectly happy if this trend continues.