As one trial ends, the next one begins.

U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos in Corpus Christi will begin hearing arguments Tuesday on one of the nation’s most stringent voter ID measures, which Republican Gov. Rick Perry signed into law in 2011.

A ruling is unlikely before Election Day, meaning that 13.6 million registered voters in Texas would still produce a photo ID this November. That hasn’t stopped Democrats from wielding the law as a campaign cudgel, particularly Wendy Davis, who has attacked Republican Attorney General Greg Abbott over his office defending the measure in court.

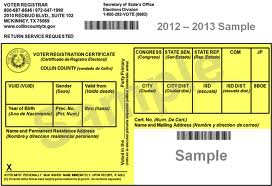

The Texas law requires voters to show one of six kinds of photo ID. A Texas concealed handgun license is valid while a college student’s university ID is not, which opponents say shows Republicans trying to imposes obstacles on voters who typically vote Democrat.

The Justice Department is taking an aggressive role in trying to dismantle the law after the U.S. Supreme Court last year threw out a key portion of the federal Voting Rights Act, which had thwarted a flurry of recently passed voter ID measures in conservative states from taking effect.

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder made Texas a top target after vowing to go into states to wring out whatever remaining voter protections he could.

Minority rights groups that sued Texas over the voter ID law say the Justice Department has added muscle — and money — since joining the lawsuit last year.

“It’s leveled the playing field,” said Joe Garza, a San Antonio-based attorney for the Mexican American Legislative Caucus. “I think the overall evidence is going to show significant impact on the minority community.”

The trial is expected to last two weeks. Although Gonzales Ramos could issue an immediate ruling from the bench that could affect the November elections, attorneys believe that is unlikely.

NPR adds some context.

The difference between this case and the one before the federal court in 2012 is that now the burden of proof is on the law’s opponents. Still, they think they might have an advantage. The case is being heard by U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos, who was appointed by President Obama.

But the voter advocacy groups also know — if they prevail in her court — the state will almost certainly appeal the decision to a federal court with a more Republican tilt. The state wants to keep the ID requirements in place for this November’s election.

All this is important, says Edward Foley, an election law expert at the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University, because there are similar voter ID laws being challenged or considered in other states, including North Carolina and Wisconsin. Those involved are watching this case to see how effective Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act will prove to be in the fight against such laws.

“That’s a major, major issue,” says Foley. “All states are bound by the obligation not to impose a discriminatory burden on voting rights on the basis of race, and so if a voter ID law [is found to have imposed] that burden … that would be very significant new voting rights law.”

Foley says it could be applied not only to ID laws, but to other things such as cutbacks in early voting. He and other experts think the issue might very well end up before the Supreme Court.

Enrique Rangel reminds us of that 2012 decision, by the DC Circuit Court, when the state and AG Greg Abbott bypassed the Justice Department to sue for preclearance.

“The State of Texas enacted a voter ID law that — at least to our knowledge — is the most stringent in the country,” the three-judge Washington court said in its 56-page opinion.

“It imposes strict, unforgiving burdens on the poor, and racial minorities in Texas disproportionately likely to live in poverty,” part of the opinion reads. “And crucially, the Texas Legislature defeated several amendments that could have made this a far closer case.”

Yes, as I’ve said multiple times, the Republican-dominated legislature went out of its way to make this law as harsh and unforgiving as it could, all in ways to inconvenience or incapacitate voting blocs that leaned Democratic. One of the more egregious examples of that was making concealed handgun licences acceptable for voter ID purposes, but not student IDs. That led to another group of plaintiffs getting involved.

Voter ID requirements and other new voting restrictions not only pose unique barriers to African-American, Latino and low-income voters, they say, but also disproportionately affect students and youth, despite the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that declares the right to vote "shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of age."

[This] week, a federal court will begin hearings over a lawsuit filed to block Texas' voter ID bill, which went into effect in 2013. Late last year, the Texas League of Young Voters, represented by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, joined the U.S. Justice Department in suing Texas over the bill, which allows military IDs and concealed handgun licenses to be shown at the polls — but not student photo ID cards.

In Texas and other states, lawmakers have typically justified leaving student IDs off the list of accepted forms of voting identification on the grounds that students frequently move so their address may not be current. But students and voting rights advocates counter that the purpose of voter ID laws has never been to verify a voter's address — it's to confirm their identity, as the photo will ostensibly prove that the voter is truly who he or she claims to be.

"We haven't heard really good rationale for [not allowing student IDs]," Dale Ho of the American Civil Liberties Union told Time magazine. "It doesn't make any sense to exclude student IDs on the basis of an address. It leads us to think the only reason why they're excluding student IDs is that they don't want students to vote."

That's exactly what seven North Carolina college students alleged was a factor in the state's passage of a passel of voting restrictions last year, including a voter ID requirement that will go into effect in 2016. Like Texas, North Carolina's law also doesn't recognize student ID cards as legitimate for voting, although military and veteran cards are acceptable. That led students to join a set of lawsuits brought by the ACLU, NAACP and the Department of Justice that were combined into one seeking to block North Carolina's so-called "monster" voting bill [pdf]. (Earlier this month, a judge denied a preliminary injunction to block key provisions of the law from going into effect for this November's election.)

I don’t believe that group is directly involved in the Texas litigation, but the North Carolina case is just as important. Hair Balls reminds us who in Houston would not be able to vote right now.

What we see here is the higher cost to participate in the voting process for people already living in poorer parts of town. If you want to vote, you must take time away from work to travel to a DPS office within the city in order to obtain a photo ID.

That gets even harder when there’s no access to personal transportation, which obviously puts low-income residents at a disadvantage. And in Houston, that disadvantage is pretty significant. The average travel time to a DPS office for a person with a vehicle, one-way, is about 10.5 minutes. Not too bad for a city as spread out as Houston. But if you’re taking a bus to a DPS office to get that photo ID, you’re looking at about 66.7 minutes worth of travel time — in one direction. Oh, and that’s not factoring in the distance from one’s home to the bus station, and from the bus station to the DPS office — which can add even more travel time.

So, it basically takes Houston’s bus-riders — i.e. folks in areas where they can’t afford a car — about 6.3 times longer to get approved ID so that they can vote. That might be a slight hindrance, no?

If you’re already poor and you can’t access your local DPS office in a feasible, cost-effective way, chances are you’ll be less likely to get an approved ID than those living in richer neighborhoods who have cars. Which means you’ll be less likely to vote.

That’s cause and effect.

That also doesn’t take into account the fact that DPS offices are generally open only during regular business hours, and a lot of the working poor don’t get paid time off, meaning that an hours-long trek to their DPS office to get the ID they need also costs them a day’s pay. Again, the Lege could have provided for these folks by funding a program to reach out to people who lack ID and help them get it without going through all that, but they have shown no real interest in that. All of which leads to the inevitable conclusion.

Suppose that you were a member of a state legislature, and you drafted a new proposed law regarding voting procedures. Further suppose that as you shopped your proposed law around, everyone you met told you that the sole effect your law would have would be to suppress voting by the poor and minority voters.

Suppose you asked for second and third opinions, but again kept hearing the same thing – that whatever your law was meant to accomplish, or claimed to combat, or was at least nominally supposed to resolve, it would simultaneously utterly and completely fail to achieve that stated objective, while at the same time limiting access to the polls for minority voters.

A law that punishes felony theft at least accomplishes the goal of punishing people who steal things. The people who are punished may be disproportionately likely to be members of a protected class, which could either be the result of social factors not considered in the drafting of the penal law, or the result of disproportionate poverty and incitements to crime that are not uniformly distributed throughout society. It could also be the result of intentional design in the penal law, but for the sake of argument, let’s assume that the law punishing theft wasn’t consciously written to disenfranchise minority groups.

In contrast, everyone who looked at the picture I.D. law before it was ever made into law said the same thing – the law addressed no actual need or concern on the part of the State, but solely accomplished one goal – limiting voting access by the poor (and disproportionately, by minorities, the elderly, and the young). That is not just an incidental consequence of the law, that is the law’s purpose, function and design. Additional picture I.D. requirements were added to the voting process in order to limit access to voting.

Everyone knows this. No one sincerely believes the alternative narrative that is offered (“voter I.D. protects against fraud”). No one on the defense believes that narrative, and (with the possible exception of some hypothetical population of credulous fools) no one in the general public believes it. The State’s attorneys have the unenviable task of dying on the hill of “electoral integrity” to salve the egos of Texas elected officials.

So if everyone (your friends, your enemies, your colleagues in the Legislature) told you the same thing, over and over again, and yet you persisted in promoting your draft law, ultimately getting it passed by a majority of like-minded self-interested legislators, wouldn’t any rational observer say that you had passed a law that was not merely accidentally or incidentally racist, but intentionally targeted at a group of voters you could not possibly hope to win over to your side?

It’s up to the judge now, and ultimately to SCOTUS. I’ll be keeping an eye on this as it goes.

While I don’t think voter fraud is nearly as big a problem as some do, there are a couple of points that keep coming back as though they were lynch pin concepts to the lawsuit. The biggest of these is the school ID and frankly, given how easy it has ALWAYS been at most colleges and universities to get such an ID, I can see why objectively some would have problems with it. In my experience, no ID is more frequently abused than school IDs, primarily as a means of drinking or getting into clubs. Whether a friend of a friend is running the ID machine at a school or you slip someone a few bucks, it is far less secure than any form of ID issued by the state such as TDL, CCW, or generic ID card.

The 10 minutes versus an hour to a DPS location is a huge stretch too; a whole hour one time is not going to greatly inconvenience anyone. If they made you go to DPS headquarters, then we could talk about inconveniences but points like this water down the overall argument and make it look like the other side is reaching quite a bit.

“What we see here is the higher cost to participate in the voting process for people already living in poorer parts of town. If you want to vote, you must take time away from work to travel to a DPS office within the city in order to obtain a photo ID.”

Every article on this subject invariably uses the same argument, as if repeating a lie often enough makes it true.

If you have a job, then you HAD to show a state id or state driver’s license AND a Social Security card to get hired. That means you HAVE a state ID or DL ALREADY. The only folks who didn’t do that are illegals working off the books somewhere for cash, and, those people are not qualified to vote, and should not be voting.

@Steven Houston I agree with you about the student ID’s being easier to fraudulently obtain. Good point.

Steven, that report on travel time to DPS offices was just for Houston. It’s well documented that there’s something like 80 or 90 counties in Texas that have no DPS office at all. In some parts of the state, you may have to travel over 100 miles to get someplace where you can get an ID that will be acceptable for voting. Oh, and amendments to the voter ID law that would have provided for more offices where an ID could be obtained were voted down. That’s the sort of thing we’re talking about.

And as far as the student IDs go, we existed for a long time as a country without ever having to show a photo ID at the polls. It’s only in the last ten years or so that Republicans have been pushing voter ID, purportedly as a way to combat fraud despite overwhelming evidence that in person vote fraud – the kind that might be deterred by voter ID laws – is practically non-existent. Meanwhile, fraud involving absentee ballots – for which no ID is needed – is by far the most common kind that actually happens, but absentee ballots are mostly cast by Republicans in this state, so the voter ID law doesn’t address it at all. There’s really no way to look at this law without seeing the bald-faced partisan motives behind it.

Charles, again, I don’t think there is any way to truly prove whether there were voting problems given the previous way the state did things but requiring a credible ID just doesn’t seem like too much to ask for to shut them up. History is replete with voting fraud examples encouraged in large part by the lack of ID programs we have come to embrace, the same for the various government largess available. The more we give to those “in need”, the more people there are willing to scam the system.

But as Bill points out, workers would have already had ID’s and I suspect those legally receiving government benefits or having a bank account would have an ID in order to obtain them, at least those eligible to vote, so as much as I think this is all catering to a core audience that sees voter fraud behind every lost election (lost to political opponents mind you, not members of their own party), I hope the courts roll their eyes, hold their noses, and just affirm that the program should stand. If nothing else, consider the idea of making some people get off their behinds to get an ID as a way of motivating them to vote too. Then address any improprieties in absentee voting with equal vigor.