There actually wasn’t all that much testimony in the HERO repeal petition trial. On Tuesday, former City Attorney David Feldman took his turn on the stand.

City Secretary Anna Russell originally found enough valid signatures but did not verify the way each page was certified. When Feldman examined the pages himself, he testified, problems were immediately apparent.

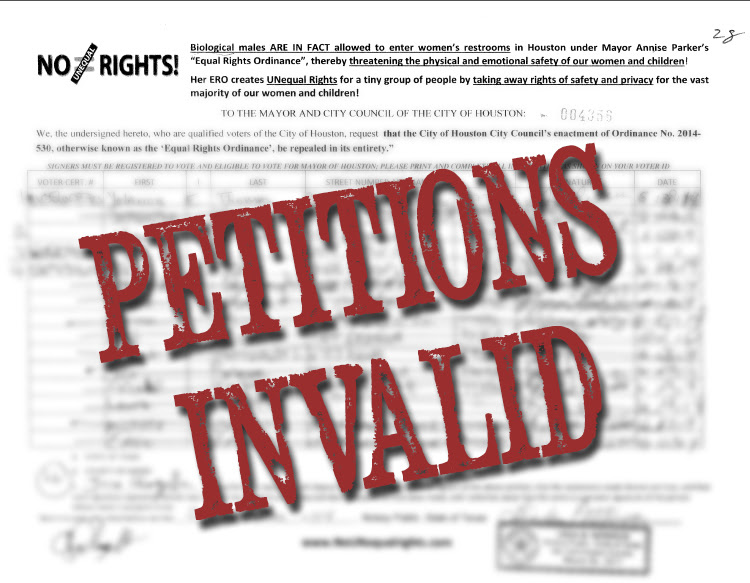

The incendiary language at the top of each petition page, attacking and misconstruing the ordinance, he said, took up so much room that the legally required oath, signature and notary lines were crammed together at the bottom of the page, Feldman said, leading many signature gatherers to err in verifying their pages.

“I believe today, as I did then, that the petition is not valid,” he said afterward.

The plaintiffs’ attorney, Andy Taylor, called Feldman’s testimony a “non-event” that “added nothing” to the city’s case.

“He and his legal team for the mayor spent all of the time trying to disqualify innocent voters from being counted in the petition rather than … trying to qualify and save their status as innocent voters,” Taylor said.

That argument comprised a key portion of his cross-examination of Feldman, in which Taylor suggested no city official knew how many valid signatures were on the pages that were not rejected. Taylor repeated that, as of December, there were 19,470 names on valid pages, which he said meant the accurate tally would be over the threshold.

Feldman countered that officials had verified all signatures on valid pages and found the tally short.

“Yes,” Feldman said. “We did the analysis.”

See here for the prior update, on Mayor Parker’s testimony. I wish I had a better feel for how things have gone, but there’s not a whole lot of other coverage out there. Feldman was not the only witness to testify on Tuesday.

As part of its defense case, the City of Houston called Janet Masson to the witness stand. She’s a forensic document examiner — with a background in handwriting analysis — who studied each of the 5,100 pages of the petition. Masson testified that she found several irregularities. For example, she said many of the signatures appear to be duplicates.

Geoffrey Harrison is the attorney for the City of Houston. He explained the importance of Masson’s testimony in an interview outside of the courtroom.

“She is showing hundreds of pages by hundreds of pages and hundreds of signatures by hundreds of signatures that there is fraud, forgery and clearly non-accidental defects,” Harrison said.

The plaintiff’s attorney, Andy Taylor, argued during the trial that even though some signatures may be duplicates, they should be counted as valid at least once, and not thrown out entirely.

Much as it pains me to agree with Andy Taylor, I don’t think it’s unreasonable for a duplicated signature to count once, if it is otherwise valid. It would be nice to know why there are so many apparent duplicates – it sure sounds to me like Taylor is admitting that there are a bunch of them – and their presence absolutely calls into question the integrity of the petitions that were submitted as a whole. Some level of sloppiness is to be expected in a petition process, but at some point you have a credibility problem.

Attorneys defending the city of Houston’s contentious equal rights ordinance concluded their case Wednesday by alleging rampant fraud in the petition opponents filed in hopes of forcing a repeal referendum on the law, and targeting pointed questions at the lead plaintiff, attorney and conservative activist Jared Woodfill.

Among the 5,199 pages petitioners submitted to the city last summer was one containing the names of Woodfill, the former longtime head of the Harris County Republican Party, and his wife, Celeste Woodfill. Woodfill printed his name in the oath at the bottom of the page to affirm both signatures were correct and collected in his presence. Testimony focused on whether Woodfill may have penned the signature next to his wife’s name and whether Woodfill’s printed name at the bottom of the page constituted a signature for the purposes of swearing an oath.

[…]

In questioning Woodfill on Wednesday, city attorneys drew on a December deposition in which his answers left some doubt as to whether his wife’s signature was authentic. The mark looked “messier” than he expected, Woodfill recalled Wednesday. Pressed on the point by one of the city’s attorneys, Alex Kaplan, Woodfill said he filed paperwork correcting his deposition immediately after speaking with his wife, and said flatly, “I did not sign for my wife.”

“I corrected that and then I talked to her about it, all right? My oath is true,” he said. “I assure you she signed it. You’re insinuating she didn’t sign it.”

The plaintiffs’ attorney, Andy Taylor, responded by calling Celeste Woodfill to the stand. She acknowledged her petition signature and her signatures on other public documents the city attorneys displayed differed greatly, but she said, “There is no doubt in my mind, that is my signature,” and had a ready explanation.

“I was holding my 30-pound son in one hand and trying to sign with the other,” she said on cross examination. “Breakfast, getting the backpacks packed, it’s a totally different situation … than sitting at a table. Any mother would understand.”

I suppose if the petition page were a loose piece of paper, and you didn’t have a hand free to hold it down as you signed it, it could be messy. On the other hand, if the petition page were on a clipboard, as is usually the case for petitions, it would be stationary as you signed it, so your signature would look normal. I say this as someone who did a lot of things one-handed back when my kids were little.

Believe it or not, that was the end of testimony in the case. Both sides made their closing arguments yesterday.

Andy Taylor, attorney for the plaintiffs, painted the trial as pitting desire of the people to vote against an all-powerful City Hall. Gesturing to the city’s many pro bono lawyers, Taylor referenced the bible.

“Help us beat Goliath,” Taylor said. “Help us beat City Hall.”

Geoffrey Harrison, attorney for the city, was less theatrical in his closing. Instead, he walked jurors through some of the pages they will be asked to consider and determine if, for instance, a circulator both printed their name and signed the bottom of the page.

“The plaintiffs have tried throughout this case to skirt the law,” Harrison said. “We don’t get to pick and choose what rules we follow.”

If nothing else, this confirms my theory of the litigation, and why the plaintiffs were so adamant about putting this before a jury: The facts are not on their side. They hope to win by appealing to emotions. Maybe it’ll work, I don’t know. I certainly hope the jury was impressed by the evidence of fraud and forgery. We’ll have to wait till they’re ready to tell us.