From Russ Tidwell, writing at Letters from Texas:

There is well-established case law around redistricting that calls for creating a new minority opportunity district anytime a compact majority of a single minority group can be established (i.e., majority Black or majority Hispanic), but a combination of the two doesn’t necessarily count.

While Texas is seeing explosive growth in its various minority populations, much of that growth is not concentrated in single minority neighborhoods. Rather, much of this population has been diffused into the close-in suburbs of our major urban counties and other small cities. Multi-ethnic communities of Hispanics, Blacks, Asians and Anglos have emerged in Mesquite, Garland, Irving, Arlington, Grand Prairie, Killeen, Waco, Sugar Land, and western Harris County.

It is literally impossible to draw compact districts here that have a majority of any single minority.

As noted in a previous post, by 2008, minority citizens in many of these naturally-occurring suburban concentrations had elected the candidates of their choice to the Texas House, and this made a difference. The House was closely divided and all minority legislators had the opportunity to be “at the table.”

The 2010 electoral tsunami swept out the minority candidates of choice in all swing districts. The resulting Anglo supermajority in the legislature attempted to make its status permanent by dismantling the districts that had given minority citizens voice. Alternatively packing and fragmenting those voters was the process. Litigation ensued.

Do those minority citizens in ethnically diverse communities have voting rights? That is what the redistricting litigation is about in large part. The State of Texas, in closing arguments at trial, says they do not. The state, in effect, says that if a minority citizen cannot be drawn in to a district with a majority of the population from a single minority group, they have no other voting rights protection. Believe it or not, that is the state’s position in federal court.

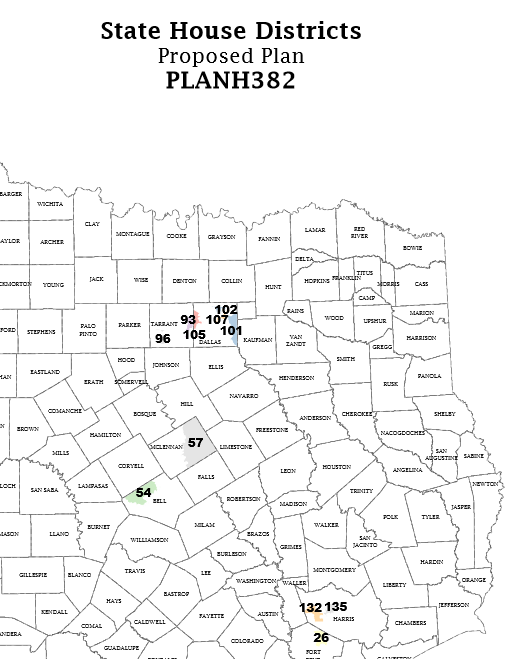

The Perez Plaintiffs published a demonstration map (view the map and view the analysis) showing eleven hypothetical State House districts in suburban Texas where this fragmentation occurred. This map reverses that fragmentation and produces eleven compact districts where minority citizens would have the opportunity to elect the candidates of their choice.

These demonstration districts have a total population of 1,834,145. Just over a million of them are Black or Hispanic (1,002,389); another 184,802 are Asian. Almost 65% of this population is minority, yet it is impossible to draw one district in this territory that has a majority of a single minority group. The population is too diffused.

This map would recognize voting rights for almost 1.2 million people who are disenfranchised under the state’s enacted plan. That is the significance of this litigation.

Tidwell notes that final arguments and briefs have been filed with the three-judge panel in San Antonio, so one presumes we will get a ruling sometime in the next few months, with the possibility of new maps being in place for the 2016 election. The Perez plaintiffs’ map and associated data can be found here. There’s also a Plan 381, which shows all of the districts that would be affected after these 11 were changed. In any event, the point is that either the state will get some number of these minority fusion districts or it won’t. That’s the question for the court. There is no election data analysis for the Perez plan, but based on the data I recall seeing for maps that got proposed during the redistricting process in 2011, it’s fair to say all 11 districts in the Perez map would be friendlier to Dems, in some cases tilting competitive but red-leaning districts blue, and in others (such as HD26) turning solid red districts into competitive ones. How likely any of this is to happen, including at the appellate levels, I don’t know. But this is where we are as of today.

I don’t want to get too far into the weeds, but in addition to showing that a single minority group is numerous enough for its citizens to form the majority of a compact geographical district, advocates must also show that the actions of white voters block or frustrate the ability of minority voters to elect their preferred candidates.

There are few new homogenous Hispanic communities where Latino citizens make up more than 50% of a district.

There is little evidence that black and Hispanic and Asian voters all team up to support each other’s preferred candidates. Here are some examples: Blacks voted for Sen. John Whitmire, Hispanics for Martinez. Blacks voted for Rep. Kevin Bailey, Hispanics for de la Garza. Blacks voted for Beverly Clark for Congress; Hispanics stuck with Ken Bentsen. Blacks supported Mayor Whitmire, Hispanics backed Hoffheinz. Hispanics supported Mayor Lanier, blacks supported Turner.