Rick Hasen, writing in Slate:

The trial court was ready to throw out the entire law, but the 5th Circuit said such a remedy went too far. The court held that when a trial court finds a law has a discriminatory effect under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, it has to keep as much of the law in place as it can while still fixing the illegal part. In this case, the appeals court told the trial court to keep the voter identification law in place but create an alternative means to vote for those who face a reasonable impediment in producing the right form of identification. For example, the trial court may order that a voter be able to vote after signing a form under penalty of perjury saying he faced a larger barrier to get an ID. The appeals court sent the case back to the trial court to figure out exactly how to soften the law.

This kind of remedy is a win for the plaintiffs, though it’s not as good as what the trial court proposed by throwing the entire law out. Other states, such as South Carolina, have softened their voter ID laws, but in practice this softening doesn’t always work well, in part because voters and poll workers aren’t aware voters can vote without the right ID if they have a reasonable impediment to getting one.

But that softening isn’t the biggest news to come out of the appeals court decision. To find it, you have to read all eight of the opinions together in light of the trial court’s finding that Texas not only violated the Voting Rights Act by passing a law with a racially discriminatory effect but that it also passed the law with a racially discriminatory intent. Upon finding a racially discriminatory intent, the trial court would be free to put Texas back under federal “preclearance” of its voting rules for up to 10 years, the kind of oversight the United States Supreme Court got rid of for a large number of states (including Texas) in the 2013 decision Shelby County v. Holder.

The appeals court divided badly in reviewing the trial court’s finding of racially discriminatory intent. Imagine that the trial court found bad intent from two baskets of evidence, Basket A and Basket B. Counting noses, a majority of 5th Circuit judges believed that the trial court’s analysis went too far in inferring discriminatory intent in considering what was in Basket A, such as statements by the law’s opponents in the state Legislature as to the intent of the legislators who passed the bills. But, again counting noses, a different majority of 5th Circuit judges believes that there is enough evidence in Basket B from which the trial court could indeed infer that Texas passed its law to discriminate against Texans who are Latino or black. It sent the case back for the trial court to reconsider the question looking just at Basket B, and a finding of racially discriminatory intent from the trial judge again seems likely.

The dissenters suggested that at worst the evidence showed an intention by the Republican-dominated state Legislature to discriminate against Democrats, not against blacks or Latinos. A majority of judges, noting an overlap among racial and partisan groups in Texas, didn’t buy it. In a place like Texas, it makes no sense to separate race and party. As the majority explained, “Intentions to achieve partisan gain and to racially discriminate are not mutually exclusive.” And as one of the judges who believed that evidence from both Baskets A and B proved Texas engaged in racial discrimination put it, if Republicans in the Texas Legislature, out of partisan motives, selected a course of action “at least in part because of, and not merely in spite of, its adverse effects on an identifiable group, that is enough” to show racial discrimination.

Zachary Roth notes that while this win wasn’t as big for the plaintiffs as it could have been, it was still pretty big.

Immediate consequences aside, Wednesday’s opinion was noteworthy for painting a picture of Texas’s Republican lawmakers as, at best, indifferent to the struggles of the state’s low-income and minority voters to get an ID. The ruling also offered firm rebuttals to many of the arguments made both by Texas in support of its law, known as SB 14, and by ID proponents more broadly. That it came from Judge Catharina Haynes, a staunch conservative — though one with a reputation for independence — writing for likely the most conservative federal appeals court in the nation, only bolstered its impact.

The appeals court affirmed Gonzales Ramos’s finding that the law’s drafters were aware that it would make it harder for minorities to vote, but they nonetheless rejected a slew of measures that would have softened its impact, largely refusing to explain why. The ruling also swiftly dispatched Texas’ claim that the plaintiffs hadn’t identified a single person who faces a substantial obstacle to voting thanks to the law, noting several people who the district court found were clearly disenfranchised by it. (News reports, including from MSNBC, have turned up many more.) And it slammed the state for devoting “little funding or attention to educating voters about the new voter ID requirements.”

Perhaps most forcefully, the opinion derisively rejected Texas’ claim that the law was needed to prevent voter fraud.

“Ballot integrity is undoubtedly a worthy goal,” Judge Haynes wrote. “But the evidence before the Legislature was that in-person voting, the only concern addressed by SB 14, yielded only two convictions for in-person voter impersonation fraud out of 20 million votes cast in the decade leading up to SB 14’s passage. The bill did nothing to combat mail-in ballot fraud, although record evidence shows that the potential and reality of fraud is much greater in the mail-in ballot context than with in-person voting.”

Haynes also noted that preventing non-citizens from voting was offered as another rationale for the bill “even though two forms of identification approved under SB 14 are available to noncitizens.”

“The provisions of SB 14,” Haynes wrote, “fail to correspond in any meaningful way to the legitimate interests the State claims to have been advancing through SB 14.”

Instead, the court suggested, the law had a different purpose. “The extraordinary measures accompanying the passage of SB 14 occurred in the wake of a ‘seismic demographic shift,'” Haynes wrote, “as minority populations rapidly increased in Texas, such that the district court found that the party currently in power is ‘facing a declining voter base and can gain partisan advantage’ through a strict voter ID law.”

The opinion also took on an argument used more broadly in support of ID laws: That they must not keep people from voting, since turnout rates have increased, compared to previous years, in elections where they’ve been used. As Haynes noted — and as voting rights advocates challenging voting restrictions have been at pains to point out from Texas to North Carolina to Wisconsin — turnout fluctuates for all sorts of reasons. “That does not mean the voters kept away were any less disenfranchised,” Haynes wrote.

Perhaps most far-reachingly, the opinion in several places starkly rejects Texas’ effort throughout the case essentially to narrow Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act so that it would bar only intentional and blatant acts of racial discrimination in voting. That’s a crusade that for decades has been pursued by numerous leading conservative legal minds, as they’ve looked to further weaken the landmark civil rights law.

Instead, the court affirmed, the law must recognize that racial discrimination usually comes in subtler forms. “To require direct evidence of intent would essentially give legislatures free reign [sic] to racially discriminate so long as they do not overtly state discrimination as their purpose and so long as they proffer a seemingly neutral reason for their actions,” Haynes wrote, “This approach would ignore the reality that neutral reasons can and do mask racial intent, a fact we have recognized in other contexts that allow for circumstantial evidence.”

Texas’s interpretation of the law, Haynes added “effectively nullifies the protections of the Voting Rights Act by giving states a free pass to enact needlessly burdensome laws with impermissible racially discriminatory impacts. The Voting Rights Act was enacted to prevent just such invidious, subtle forms of discrimination.”

Reading Section 2 in the way Texas recommends, Haynes wrote, would “cripple” the Voting Rights Act, and “unmoor” it “from its history and decades of well-established interpretations about its protections.”

Stop for a moment and savor the irony here. Texas Republicans passed the odious and now-dead HB2 not just to effectively outlaw abortion in the state, but also as part of a national strategy to render null Roe v. Wade. Indeed, one of the judges at the same Fifth Circuit basically dared SCOTUS to overturn Roe in her opinion. Instead, the ruling by SCOTUS not only upheld Roe v. Wade (more accurately, it upheld Planned Parenthood v. Casey), it basically cut off at the knees the very strategy that anti-abortion forces had been using with HB2 and elsewhere in the country. Large swaths of anti-abortion legislation fell or are falling as a result. Now here with voter ID, the legal strategy in its defense was to gut Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Not only did that fail with a giant thud, Texas may wind up back under preclearance because of how voter ID was adopted. In both cases, the railroading of the opposition to these bills and the utter indifference to any and all objective facts surrounding their effect came back to bite the state and the Republicans responsible for these laws squarely on the ass, and may do more damage to their cause than anything the Democrats (who fought like hell against both bills despite being completely outgunned) could have done. Bravo, ladies and gentlemen. Bravo, Rick Perry and Greg Abbott and David Dewhurst and Dan Patrick and Ken Paxton. You all may wind up making a positive contribution to this state’s future after all.

Anyway. We now know what the “softening” of voter ID may look like. Hasen again:

It is further ORDERED that any plan for interim relief must include terms regarding the following:

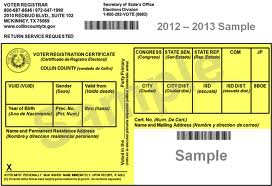

- All persons who have SB 14 ID or who have the means to get it in time for the November 8, 2016 election must display that ID in order to vote;

- No ID that is easily counterfeited may be used in any ameliorative provision;

- There must be an impediment or indigency exception, which may include reinstatement of the ability to use the voter registration card for such voters;

- The State must educate the public in a meaningful way about the SB 14 ID requirements and all exceptions to those requirements that are set out in the original law and in the interim plan adopted by this Court;

- The State must educate and train workers at polling places to fully implement the resulting plan; and

- The plan shall address only the discriminatory effect holding of the Fifth Circuit’s opinion and shall not include relief that would be available only in the event that this Court finds, upon reweighing the evidence, that SB 14 was enacted with a discriminatory purpose.

Emphasis mine, and you can see the order here. I don’t have any faith in the state’s motivation to “educate the public”, but perhaps the threat of sanctions may light a fire or two. We’ll see how it goes. More from Hasen is here, and Texas Standard, Reuters, the Trib, the Chron, and the Current have more.