That’s a question that is alluded to but not directly addressed in this story.

“This is how the land is supposed to act,” said Mary Anne Piacentini, executive director of the Katy Prairie Conservancy, a nonprofit land trust. “It’s supposed to absorb water and filter out pollutants. It’s not supposed to send it roaring into the rivers and bayous and homes.”

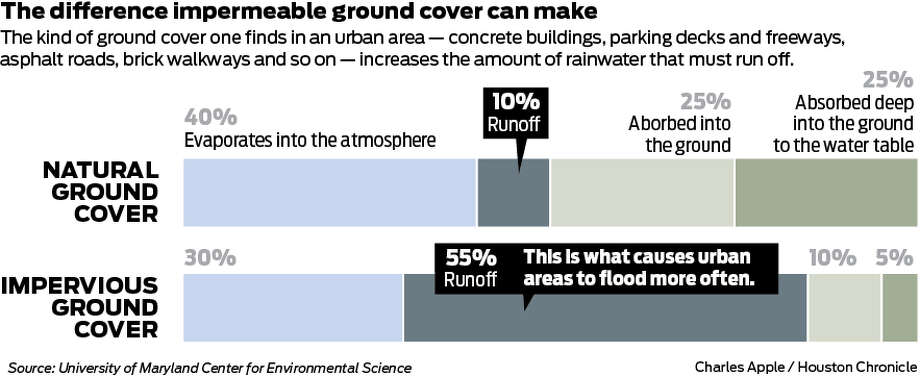

In the greater Houston area, though, the staggering increase of impervious surfaces — roads, sidewalks, parking lots, anything covered with asphalt and concrete — has exacerbated the effects of flooding as development in the region has exploded. When land is covered by these surfaces, it loses ability to act like a sponge and soak up water. Things are further complicated in flat-as-a-pancake Houston, where much of the soil is heavily compacted and acts like pavement anyway, sending sheets of storm water to the nearest low-lying area.

A recent analysis of federal satellite data by the Houston Advanced Research Council for the Houston Chronicle shows that 337,000 acres of 1.1 million acres in Harris County were covered by impervious surfaces in 2011, the most recent year of data. That dwarfs surrounding counties, but the analysis shows many are catching up as the onslaught of development continues pushing from the city farther into the suburbs.

Between 2001 and 2011, Fort Bend County, for example, had a 53 percent increase in impervious surfaces, more than twice the percentage increase in Harris County during the same period. Waller County, home to much of the Katy Prairie, saw a 17 percent increase.

That kind of development comes with a price, namely the loss of the region’s natural landscape, including wetlands, prairies, coastal marshlands and forests, and thereby a greater risk of flooding. Even with federal regulations in place to preserve wetlands, the 14-county Houston region lost more than 54,000 acres of wetlands between 1996 and 2010, according to HARC’s analysis.

“Pitiful,” said John Jacob, a Texas A&M University professor and director of the Texas Coastal Watershed Program.

As large tracts of undeveloped land have been transformed by new roads, homes and businesses, city and county planners have relied almost exclusively on detention basins — often referred to as detention ponds — to solve the water runoff problem created by the region’s vast asphalt and concrete surfaces.

Detention basins are man-made structures designed to capture storm-water runoff and temporarily store it. Harris County first began requiring them of developers in the early 1980s, and neighboring counties quickly followed. Today, each county in the region has hundreds of the ponds, both dry and wet.

However, these detention requirements have fallen short in attempting to tackle the source of the flooding problem because they do not require developers to eliminate runoff from their projects.

Many Houston-area homeowners blame inadequate storm-water mitigation rules for their flooding woes. City and county officials disagree, but concede it’s difficult to untangle the effects of new development, flood control projects and climate change when trying to determine the culprit for the region’s worsening flood problem. The issue came to a head recently for a group of west Houston residents who sued the city a couple of months ago claiming it is allowing developers to circumvent storm-water safeguards.

“I can show you on any individual project how runoff has been properly mitigated,” Montgomery County Engineer Mark Mooney said. “Having said that, when you see the increase in impervious surfaces that we have, it’s clear the way water moves through our county has changed. “It’s all part of a massive puzzle everyone is trying to sort out.”

This story is part five of a series, for which earlier and related stories are here. It notes that Fort Bend appears to be doing better than Harris County in terms of mitigation, as they had our example to learn from and mandated more stringent rules for its detention ponds. Fort Bend has also seen an awful lot of its permeable land become impervious in recent years, so who knows how well that will hold up as development continues. The scary thing to me is the shrinking of the Katy Prairie, which does so much of the heavy lifting for the region. It’s not like we can make more of that, and it’s getting harder to find space for the often-inadequate detention ponds that we build here in Harris County. It would help if we had fewer 23-inches-in-14-hours type rainstorms, but the feeling I get is that we’re in a new normal, and we need to figure out how to cope with that.