Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern says that Tuesday’s arguments about whether Texas’ voter ID law was enacted with discriminatory intent or not went well for the plaintiffs, and not for the state or its new buddies in the Justice Department.

Tuesday’s hearing was supposed to be all about the question of intent. But the DOJ’s last-minute move to side with Texas rather than the coalition challenging the law threw it for a loop, necessitating a discussion of the agency’s new position. John Gore, the deputy assistant attorney general for the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, spoke briefly, urging the court to dismiss the discriminatory intent claim. (The agency’s acting head of the Civil Rights Division, Thomas Wheeler, recused himself because he advised Texas legislators as they wrote the bill. Small world!) Gore pointed out that Texas is considering an amendment that will allegedly address the legal problems with the bill, SB14.

“If it follows through,” he said, “and we are hopeful it will, that resolves this case.”

But does it? Judge Ramos wasn’t so sure.

“How,” she asked, “does a new bill affect a ruling on discriminatory purpose on SB14?” After all, an amendment can’t alter the legislature’s intent in passing the original bill. (The Trump administration may face a similar problem in its efforts to scrub Islamophobia from its next travel ban.)

“It creates a new legislative mosaic,” Gore said, with lots of feeling, if not much logic. “It paints a new picture of Texas’ intent with regard to voter ID.”

Chad Dunn, a member of the legal team representing the plaintiffs in the case, tried his best not to look aghast and very nearly succeeded.

“The Voting Rights Act does not deal around the edges,” he said in rebuttal to Gore. “It requires courts to strike down a discriminatory law and all of its tentacles. Texas may change the staging or the dress of SB14, but the underlying architecture remains.”

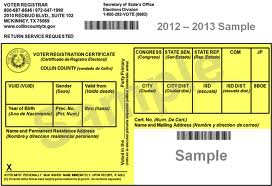

To Dunn, the key problem with SB14 is the limitations it places on the forms of ID voters may use at the polls. A handgun license, for instance, is sufficient to cast a ballot; a student ID is not. Minorities are significantly less likely to have the required IDs than whites. Dunn argues that SB14 was crafted with the aim to create “a disparate impact on Latinos.” Even if Texas remedies this problem, its original bill may still have been enacted with discriminatory intent, meriting federal oversight of future voting-related laws.

In her previous ruling, Ramos laid out a comprehensive case demonstrating why the legislature had intentionally endeavored to restrict the suffrage of minority voters. On Tuesday, attorneys for the plaintiffs took turns reciting her reasoning back to her. The argument here is not rocket science. In support of SB14, the Texas legislature professed fears about voter impersonation that were unsupported by evidence. It also approved IDs that minorities are much less likely to have and rejected amendments designed to lessen the bill’s impact on minorities. Gov. Rick Perry declared the bill an “emergency item,” allowing the legislature to rush it through committee to an up-or-down floor vote, altering or suspending multiple procedural rules along the way. And it did all this in the face of dramatic demographic changes that could give minorities unprecedented influence over state representation.

In short—as Ezra Rosenberg, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, said on Tuesday—“your honor, and the United States, got this right the first time around.” The court, Rosenberg said, “may infer from these shifting and tenuous rationales that there is pretext at work.” There is, he alleged, “a mountain of evidence” that Texas acted with racist intent, even if it is all circumstantial. Janai Nelson, a lawyer with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, hit the same themes. “An overwhelming majority of factual findings unassailably supports your previous opinion,” she told Ramos. “The legislature designed SB14 with surgical precision to discriminate against minority voters. Republicans chose IDs that that Anglos were more likely to possess and excluded IDs minorities are more likely to possess. Impersonation fraud is largely mythical.” And “this aggressive fixation on an illusory problem” is evidence of unlawfully discriminatory intent.

Up until this point, Ramos remained mostly quiet, though she took extensive notes. When Angela Colmenero stood up to argue on behalf of Texas, the dynamics shifted dramatically. Colmenero, aided by a nifty PowerPoint presentation, explained that in passing SB14, the legislature was acting upon extensive evidence that voter impersonation was a serious problem in Texas. Ramos suddenly leaned forward, looking genuinely confused.

“Why was this not introduced at trial?” she asked, referring to the lengthy bench trial she held in 2014 during which Texas could not prove that voter fraud was real. “Texas,” she continued, “did not present any evidence about any of these things.”

Colmenero admitted that the purported evidence was really just testimony in House and Senate committee hearings, testimony that was not supported by any proof.

“But that’s all hearsay,” Ramos observed. “People saying X, Y, Z—that’s not evidence for a trial court. ‘So-and-so’s [deceased] grandfather voted’—that’s not court evidence.”

See here for the background. I Am Not A Lawyer, but having the judge lecture you about standards of evidence seems like an indication that your case is not going well. Nonetheless, as the Express News notes, Judge Ramos has asked for briefs on how the voter ID 2.0 bill will affect the case, with a March 21 deadline. We’ll see what happens then. The Brennan Center, the NYT, and the Chron have more.

Colmenero certainly did not endear herself to the judge presenting the GOP’s lying crap sandwich on the fiction of in person voter impersonation ID fraud