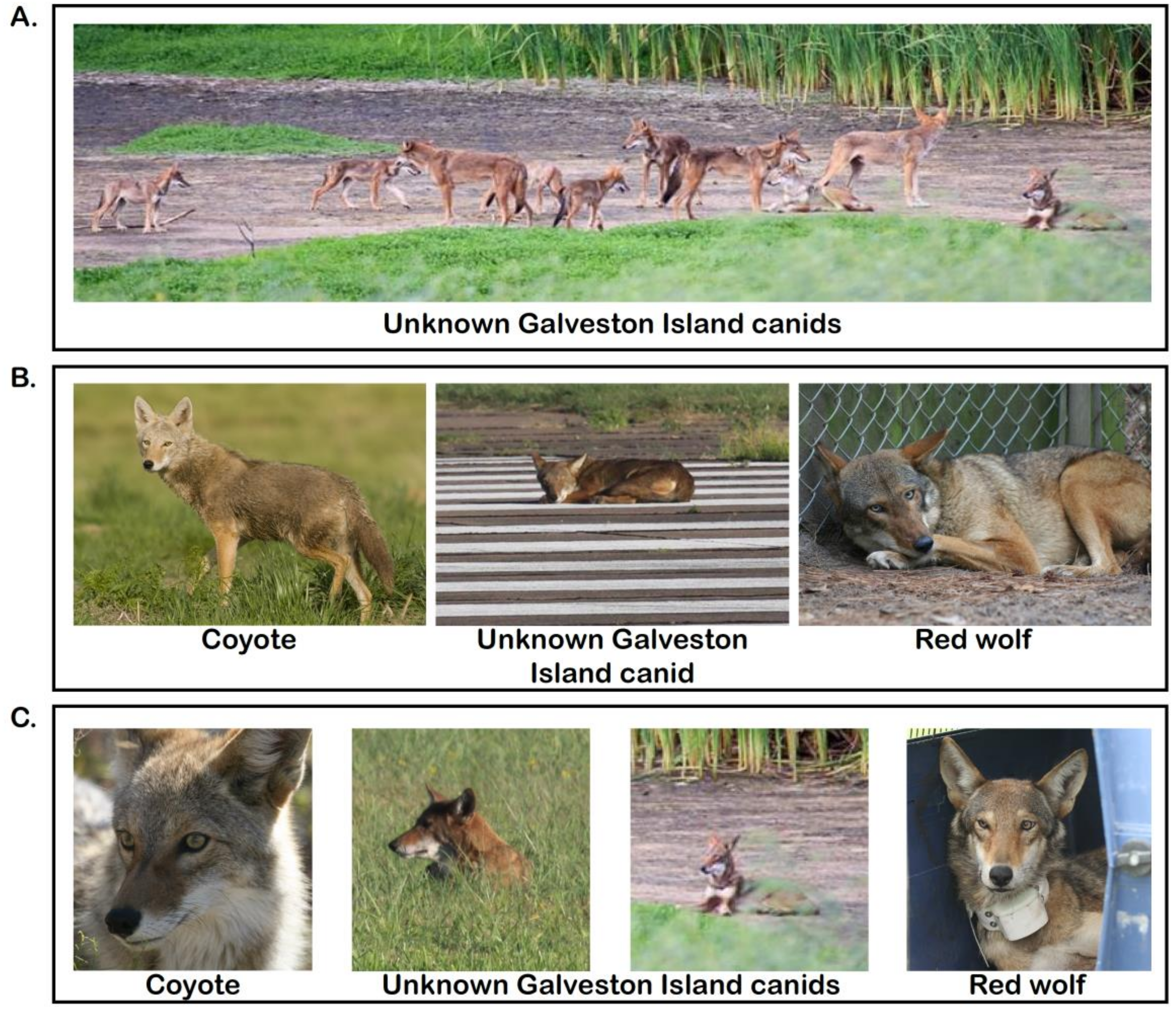

The coyotes Ron Wooten spotted on Galveston Island’s west end had eye-catching dark, reddish fur and long, slender builds. In the golden dusk of that July evening in 2013, about a dozen of the animals rested in what appeared to be a wetland dried by a seasonal drought.

These canids — mammals of the dog family — looked different. Most coyotes that inhabit this region have gray or pale-brown fur. And while coyotes typically scavenge alone or in pairs, these appeared to be traveling and interacting as a pack.

Wooten had a hunch he had stumbled onto something more important than satisfying his hobby as a wildlife photographer.

“They didn’t look like coyotes at all. I thought they actually looked like a big Great Dane or something like that,” Wooten said. “I looked at some images of red wolves and it kind of looked like they might have been leaning more towards red wolves than coyotes, so that’s when I started pursuing somebody to take a look at these animals.”

Nearly six years later, Wooten learned that his photographs played a significant role in a groundbreaking genetic study released in December by a group of scientists led by biologists from Princeton University. The study suggests that canids native to Galveston Island carry DNA elements of the red wolf, an animal declared extinct in the wild nearly 40 years ago but whose ancestry has endured in parts of the eastern United States and Gulf Coast, including southern Texas and Louisiana.

Red wolves inhabited the southeastern United States before being declared extinct in the wild in 1980 due to habitat loss, predator control programs, disease, and, ironically, interbreeding with coyotes. A captive breeding program developed in the 1970s helped stave off total extinction, with 14 red wolves able to reproduce.

[…]

Several months after spotting the pack of coyotes in Galveston, Wooten, a regulatory specialist for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, spotted two dead coyotes with similar reddish fur on his commute along FM 3005. Intrigued, Wooten scooped up the remains, hoping the carcasses might pique the interest of someone who studied wolves and coyotes professionally. He preserved the tissue samples the only way he knew how — in his freezer.

“Of course, my wife loved that,” Wooten said.

Several wildlife agencies rebuffed Wooten before he finally connected with a group of wolf biologists who put him in touch with Bridgett vonHoldt, a biologist at Princeton University. VonHoldt had been studying genetics shared between North American canids for a number of years, and Wooten’s tissue samples and photos presented possible evidence of “ghost alleles” — surviving red wolf genes different from those of the red wolves in zoos or those in the wild in North Carolina.

VonHoldt, in an interview conducted via email, said it was “phenomenal” that Wooten had both pictures and tissue samples of the canids found in Galveston. The eye-catching photos he took of the pack of coyotes with reddish fur caught her her interest.

“Coyotes have a wide range of variation in colors and markings,” vonHoldt said. “But the photo from Ron just somehow caught my interest as being unique in a very specific way.”

VonHoldt and her team extracted and processed the DNA from Wooten’s samples and compared it to each of the legally recognized wild canid species in North America, including samples from 29 coyotes from Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas; 10 gray wolves from Yellowstone National Park; 10 eastern wolves from Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario; and 11 red wolves from the captive breeding program.

They found that the Galveston Island animals were more similar to captive red wolves than to typical southeastern coyotes — one of Wooten’s samples was 70 percent red wolf, while the other was 40 percent red wolf.

The study is here if you want to know more. I don’t have anything to add, I just love stories like this.