I had a post all ready to go yesterday with more on the bill to redistrict the appellate courts, and then this happened on Thursday night:

.

#SB11 redistricting the Texas appellate courts from 14 to 7 has been withdrawn. @joanhuffman, who didn’t respond to my comments requests, kind of explained the reason for secrecy around the bill at the end of graph 1. I’ll be doing a story about this tomorrow. #appellatetwitter— Katie Buehler (@_katiebuehler) 8:33 PM – 08 April 2021

This is not the end of it – there will be at least one special session on legislative redistricting, after all – but whatever does happen, it won’t be in this session. So the post that I had queued up for Friday morning became out of date, and so here we are. The original post is beneath the fold because it’s still worth reading, so click on for more. Whatever made this delay happen, I’m glad for it. Hopefully we will get a better bill out of this in the end, but we can’t take that for granted. The Chron story from Friday about this is here.

I know I shouldn’t be surprised by stuff like this, but I still am.

Texas judges and Democratic members of the state Senate Jurisprudence Committee were largely excluded from the drafting of a controversial proposal to dramatically change the makeup of the state’s intermediate appellate courts and kept in the dark about its details, emails and interviews show.

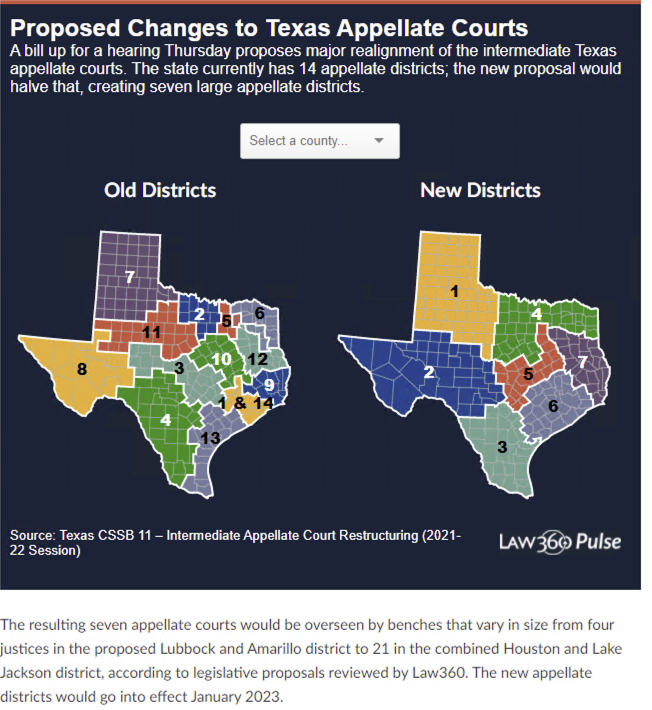

The proposal was laid out in a committee substitute for S.B. 11, which initially proposed only minor changes to appellate court jurisdiction. It calls for consolidating the 14 existing appellate courts into seven courts that would, for example, lump together Dallas and Austin and create sprawling districts with benches as big as 21 judges in Houston and Lake Jackson.

The 14 chief justices of the state’s intermediate appellate courts caught wind of the plan for a systematic shakeup in early February on a Zoom call with state Sen. Joan Huffman, R-Houston, who leads the Jurisprudence Committee. But they got no details of the plan until less than three days before the committee held a two-hour hearing on the plan and sent it to the full Senate, despite strong opposition from sitting judges and practicing lawyers.

The full text of the committee substitute bill, now referred to as C.S.S.B. 11, wasn’t distributed until the night of March 31, less than 12 hours before the public hearing started.

“That’s what we call agenda control,” said Mark Jones, a professor of political science at Rice University in Houston.

[…]

Huffman did not respond to repeated requests for an interview with Law360 since March 31 or answer questions about the bill and its drafting.

During the April 1 hearing on the bill, all but one of about 30 witnesses spoke against the change. More than a dozen intermediate appellate judges testified against the bill during the hearing, saying it would create far more problems than it would solve, particularly coming on the heels of a pandemic that will have lasting effects on the court system.

The bill passed out of committee by a 3-2 party-line vote.

Jurisprudence Committee Vice Chair Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa, D-McAllen, pointed out at the public hearing that he, his fellow lawmakers and the justices only had a few days to review the new bill. Huffman replied at the hearing that the details of the bill were distributed “when they were ready.”

“I did talk to the justices and then otherwise I just worked on the data with my lawyers here and came up with a map that met all the needs of the objectives that we talked about,” Huffman said at the hearing.

The committee’s other Democratic member, Sen. Nathan Johnson, D-Dallas, a counsel at Thompson & Knight LLP, asked Huffman if she held any stakeholder meetings while developing the consolidation plan.

Huffman said her bill was based on data provided by the Office of Court Administration on the state’s docket equalization program that transfers cases to even out workload among the intermediate appellate courts. The bill keeps in place the docket equalization program. Huffman has said the changes will make the intermediate appellate courts more efficient and cure knotty court splits, all while expanding Texans’ access to justice.

Johnson, who was elected to the state Senate in 2018, told Law360 in an interview that this was not the first time substantial changes have been made to bills “on effectively no notice.” But he said the response from the 16 intermediate appellate justices at the April 1 public hearing, many of whom traveled on short notice to testify in person, speaks volumes.

“I think the justices felt that this was an act of politics that interfered with what shouldn’t be a political realm,” he said. “For a complete overhaul to be imposed on them, without consulting them, I think offended them. Of course it offended them.”

See here and here for the background. Everything about this, from the lack of information about the bill before it was debated to the disregard for the opinion of the justices to Sen. Huffman’s refusal to answer any questions from the reporter, is just arrogance on a grand scale. Huffman – and presumably the rest of the Republicans in the Senate – see a problem they want to solve, which is that too many Democrats have been getting elected to appellate court benches, and so they set about it without giving a damn about anyone else. And why not? They figure they have the votes – Prof. Jones is quoted in the story saying that maybe House Speaker Dade Phelan will want to dial this back because he wants to maintain a cordial relationship with Democrats in his chamber – and they don’t fear any electoral consequences. And the reason they don’t fear electoral consequences is because in a couple of months they’ll get to redraw their own districts, and we all know how that is going to go. They get what they want, and the rest of us can go pound sand. Is this a great country or what?

Good. This is an epically bad idea. This would be a radical overhaul of appellate courts that slowly developed over many decades into their current structure. They are functioning well. The system may need some tweaks but any change should include transparency and input from all stakeholders. In 1980, the last time these courts experienced significant structural change, it came about with input from experts, justices, legislators, and the public. That’s the right model.

“This would be a radical overhaul of appellate courts that slowly developed over many decades into their current structure. They are functioning well.”

What if we just appointed a commission to study the idea, like Biden did, to study adding more SCOTUS judges? It’s just a study, what could it hurt?

Forgot link:

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/biden-appoints-commission-study-adding-seats-term-limits/story?id=76973903

Looking forward to the conclusions from Biden’s bipartisan commission.

In Texas, we had a commission appointed in 1980 to consider how our courts of civil appeals should be restructured so they could decide criminal cases. By the end of the year, we had 29 new court of appeals justices (from 51 to 80). Governments can do things to make this better. Partisan redistricting of the courts of appeals isn’t needed.

There were very compelling reasons for SB 11 to be killed (though there is no guarantee that it won’t be revived in some form at a later point).

The official rationales for the appellate system “reorganization” through Senator Huffman’s sneaky Judiciary Committee Substitute Bill were hogwash, and the consequences of going from 14 separate COA to 7 would be unpalatable for all incumbents; Republicans included. Hence the widespread backlash among stakeholders and the vociferous opposition by judiciary members as witnesses notwithstanding the extremely short notice of the hearing.

The primary beneficiaries of the appellate system revamp would instead be former Republican justices, who would have a chance to be re-elected in the newly gerrymandered GOP-majority appellate districts

EFFECT ON EXISTING COA OPERATIONS

On transition day, each of the justices still in office would end up on a different court, and each of the new courts would have the institutional legacies and precedents from two or more no-longer existing courts that merged into the larger district and its new enlarged court. To the extent there is a problem with conflicts among the jurisprudence of the 14 COAs, those would become more acute among the new mega-courts, which would then have to resolve them in the first instance before the SCOTX would even get a chance to do so. The party unsatisfied with a panel decision that could have gone either way (due to conflicting precedents inherited from the pre-merger COAs) would then have reason to seek a different outcome through an en banc motion, which would then require each member of the entire mega court to look at additional cases that had been assigned to a different panel, thereby increasing the caseload for each member. Ergo, less efficient.

Additionally, local rules and internal operating procedures would have to be rewritten and court-specific conventions of abolished COAs ditched or harmonized to create consistency on the seven successor courts. Different COAs currently do not even issue their opinion in the same format. Nor are the docketing practices of the 13 clerks uniform.

BIGGER PROBLEMS AHEAD

Considering the existing backlog caused by the COVID pandemic and the postponement of in-person trials, and the forthcoming surge in appellate caseloads around the state that will follow resumption of trials, the reorganization of the appellate court system would be a nightmare from the logistical and administrative standpoint alone.

And docket equalization transfers would still be necessary because of the unusual circumstances in 2020 under judicial COVID emergency orders, which resulted in widely disparate backlogs in the trial courts in different areas of the state. A backward-looking simulation of how historical appeals would have been allocated and processed under 7 as opposed to the 14 that actually heard and decided them is rather meaningless.

In any event, the transfer of cases among COAs is not even a problem for the jurisprudence of the state because the receiving court is required to follow the precedent(s) of the sending court in the event of a conflict between the two courts. Senator Huffman and the bill analysis authors failed to acknowledge this important detail.