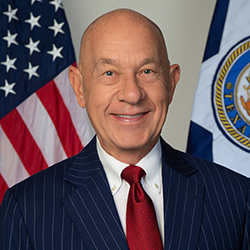

Ann Harris Bennett

The elected official in charge of Harris County’s voter registration and tax collection appears to have been absent from her office for years, last swiping her ID to enter the county building in late 2020, county records show.

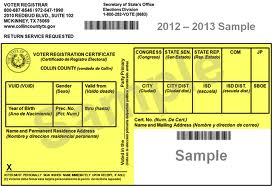

First sworn into office in 2017, Tax Assessor-Collector Ann Harris Bennett is tasked with a wide array of duties that affect nearly every Harris County resident, from collecting billions of dollars in property taxes to processing millions of vehicle registrations and title transfers every year. As the county’s voter registrar, she also oversees voter registration and maintains records for over 2.5 million voters.

In October 2023, Bennett announced that she would not seek a third term, citing a desire to focus on her family and health. The retiring official, however, still needs to lead her office in fulfilling its election duties through this year’s high-stakes presidential election cycle, including assisting voters with any registration issues that may arise.

Her prolonged absence from public view raises questions about what she has done since she was reelected in 2020, when she appears to have stopped showing up at the office. She has also hardly corresponded via email and missed a string of key public appearances last year while state Republican leaders targeted Harris County’s election process.

[…]

Last year, the state Legislature took unprecedented steps to change Harris County’s election procedures, abolishing the elections administrator’s post and returning voter registration tasks to the tax assessor-collector’s office. Bennett was not seen during that time, while the other affected elected official, County Clerk Teneshia Hudspeth, offered guidance to county leaders and the public.

Annette Ramirez, the Democratic candidate vying to become the next tax assessor-collector, said Bennett should have done more to improve internal processes and interact with the public to ensure “we don’t give Austin an opportunity to say that we haven’t done a good job.”

“You, as a public elected official, are the face (of the office), and so you’ve got to show up. You’ve got to make sure that we are being transparent, communicating with the public…That’s the job,” Ramirez said, adding she would go to work every day if elected.

Steve Radack, the Republican candidate in this year’s tax assessor-collector’s race, spoke in Bennett’s defense. He said every manager has a different style, and over the years, he has also seen other government officials who do not always show up to work.

At the same time, Radack vowed to be responsive to constituents and to actively champion the policies he believes in if elected.

“My presence will be known,” he said.

For what it’s worth, I interviewed her in January 2020, as she was in a contested primary. She was still making occasional trips into the office at that time. My best guess here, and this is just my own guess, is that there’s a health issue at the root of this. Among other things that might explain why there’s no explanation being proffered, as people don’t want to speak out of turn if Bennett herself hasn’t said anything publicly. Again, that is all 100% my speculation. Maybe we’ll know more some day, maybe we won’t.

The good news is that the staff at her office are doing a good job – no one raised any complaints in this article, and I’m not aware of any recent news about issues there, though as noted there were some before 2020, in her first term. I’ve heard some grumbles about her office not doing more about voter registration – that was a subject I explored in this year’s interviews with the primary candidates – but that was about how extensive and energetic the outreach was, not about how the nuts and bolts were being done. It’s a little weird that this question is coming up now, as her term nears its end, but one way or another we’ll have a clear point of comparison soon enough.